What is Theravāda?

Theravāda (Pali: thera “elders” + vāda “word, doctrine”), “Doctrine of the Elders”, is the teaching system of Buddhism that draws its scriptural motivation from the Tipitaka, or Pali canon, which scholars generally approve possesses the earliest existing record of the Buddha’s instructions.[1] Theravāda is the most commonly acknowledged name of Buddhism’s oldest surviving school.[2] The school’s followers, termed Theravādins, have preserved their version of Gautama Buddha’s preaching or Buddha Dhamma in the Pāli Scriptures for over two millennia. In contrast to “Northern Buddhism,” which migrated northwards from India into Tibet, Japan, Korea, and China, Theravada is also designated as “Southern Buddhism.”

The Buddha, the “Fully Enlightened One,” himself indicated the religion He founded Dhamma-Vinaya, “the doctrine and discipline,” in reference to the two rudimentary aspects of the moral and spiritual instructing system he expounded. To furnish a social structure corroborative for the practice of Dhamma-Vinaya and to preserve the Pāli scriptures for descendants, the Exalted One formulated the Buddhist order, the Sangha, which persists to this day to convey His teachings to succeeding generations of lay devotees and monastics.

History

The Theravāda lineage derives from the Vibhajjavāda, a division that arose within the Sthāvira nikāya—one of the two central orders that emerged after the first schism in the Indian Buddhist community. Theravāda origins trace their school to the Third Buddhist Council when noble elder Moggaliputta-Tissa is stated to have compiled the Kathavatthu, a significant work that identified the Vibhajjavāda doctrinal position.[3]

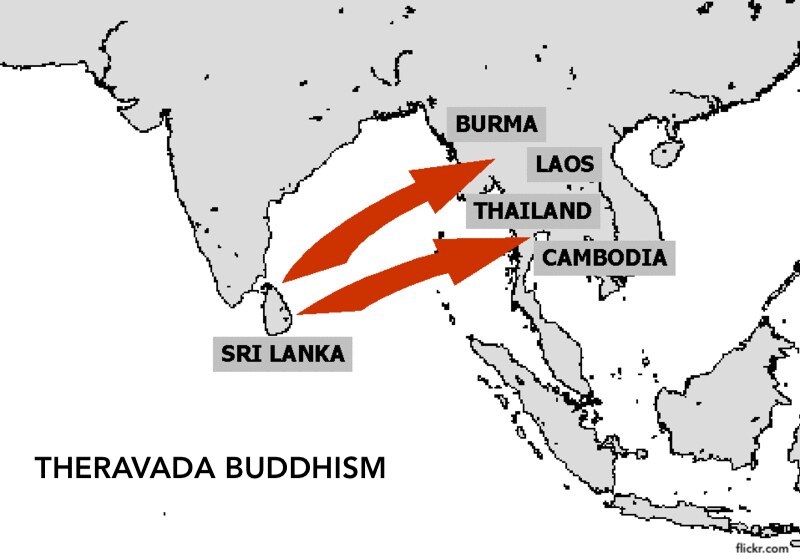

Theravāda sect commenced establishing itself in Sri Lanka from the 3rd century BCE onwards. The Pāli Canon was composed in Sri Lanka, and the sect’s commentary literature was promoted. From Sri Lanka, the Theravāda Mahāvihāra orthodoxy was subsequently disseminated to Southeast Asia.[4]

For many centuries, Theravāda Buddhism has been the predominant and official religion of continental Southeast Asia (Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia) and Sri Lanka. It is also learned and practiced by minorities in India, Nepal, Bangladesh, North Korea, the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, and China. The diaspora of these groups, along with converts worldwide, also embrace and apply Theravāda Buddhism. These days, Theravādins number has been growing around the world, and during the past few decades, Theravāda tradition has initiated to take root in the West and the Buddhist revival in India.

Pāli Canon

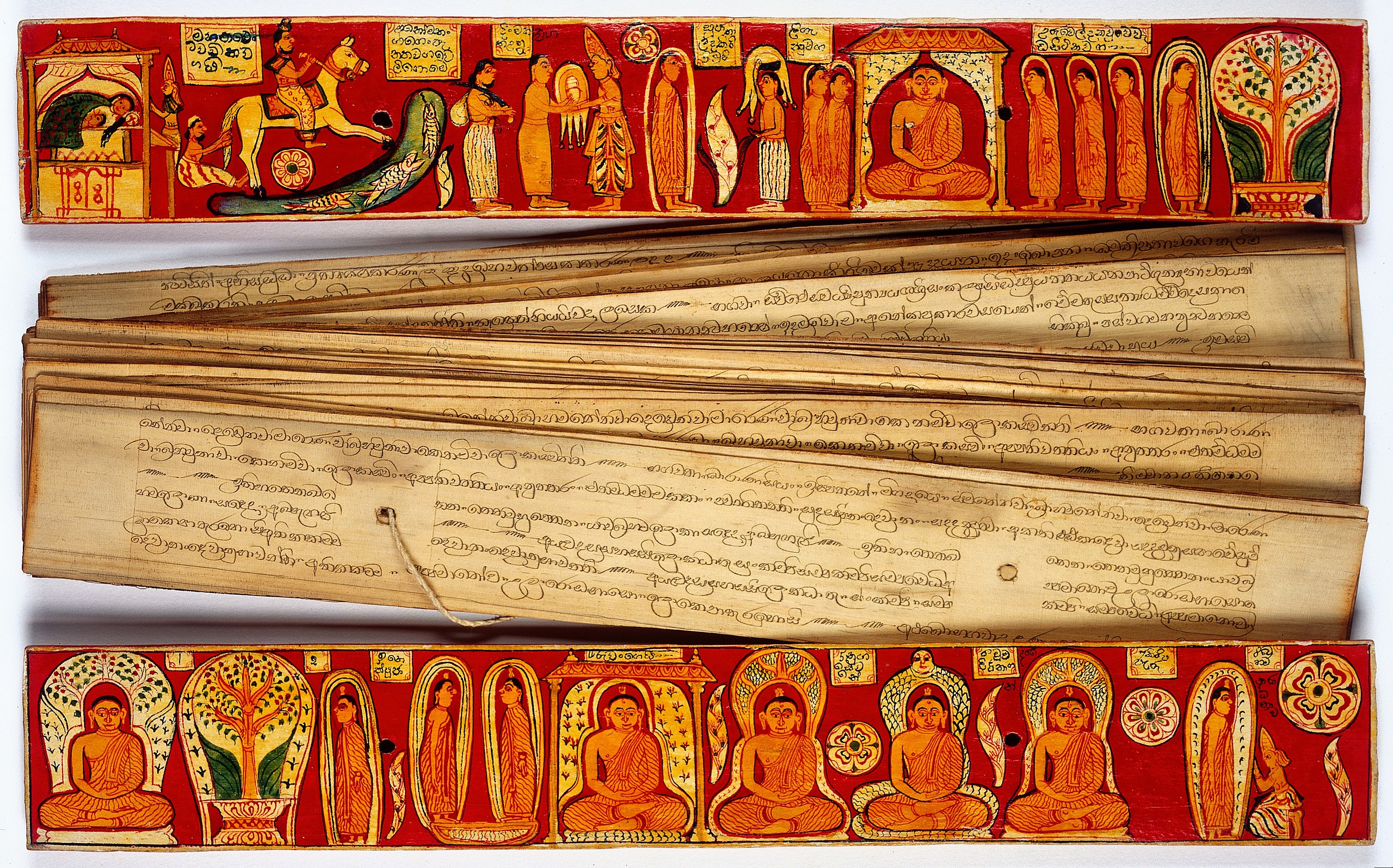

The Pāli Canon is the most complete Buddhist scripture documented in a classical Indian language, and Pāli is indicated as the school’s sacred language. Theravāda tends to grow conservative in the first two baskets—doctrine (pariyatti) and monastic disciplinary rules (vinaya)—in contrast to Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna.[4] According to Kate Crosby, for Theravāda, the Pāli Tipiṭaka signifies “the highest authority on what constitutes the Dhamma (the truth or teaching of the Buddha) and the organization of the Sangha (the community of monks and nuns).”[5]

Pāli, the language of the Tipiṭaka, is a middle-Indic language that constructs the central religious and scholarly language in Theravāda.

This language may have developed out of differing Indian dialects and pertains to, but is not the same as, the ancient language of Magadha.[6] Particularly, Theravāda is one of the first Buddhist traditions to commit its Tipiṭaka to writing.[7] The recession of the Tipiṭaka, which persists today, is that of the Sri Lankan Mahavihara school. There are varying editions of the Tipiṭaka, and some of the primary modern editions incorporate the Pali Text Society edition, published in Roman script, and the Burmese Sixth Council edition, published in Burmese script. The Pāli Tipitaka encompasses three baskets: the Vinaya Pitaka, Sutta Pitaka, and Abhidhamma Pitaka. The Theravāda sect has traditionally held the doctrinal position that the Realized One himself actually articulated the canonical Abhidhamma Pitaka.[8]

Note

Kathāvatthu is the fifth of the seven collections of the Abhidhammapiṭaka Pitaka.

References

[1] Swearer, D. K. (2006). Buddhist Religions: A Historical Introduction. By Richard H. Robinson, Willard L. Johnson, and Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff). Wadsworth/Thomson, 2004.

[2] Gyatso, Tenzin (2005), Bodhi, Bhikkhu (ed.), In the Buddha’s Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon, Somerville, Massachusetts: Wisdom Publications.

[3] Berkwitz, Stephen C. (2012). South Asian Buddhism: A Survey, Routledge, pp. 44-45.

[4] Prebish, Charles S. (1975), Buddhism – a modern perspective, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

[5] Crosby, Kate (2013), Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity, p. 2.

[6] Norman, Kenneth Roy (1983). Pali Literature. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 2–3.

[7] Harvey, Introduction to Buddhism, Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 3.

[8] James P. McDermott, Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume VII: Abhidharma Buddhism to 150 A.D. p. 80.

Sayalay Vijjāñāṇī (Tue Minh)