The development of ānāpāna-sati (mindfulness-of-breathing) is taught by The Buddha in the Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna-sutta.[1] He begins:

And how then, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu abide contemplating the body as a body?

Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu (gone to the forest, or gone to the foot of a tree, or gone to a secluded place) sits down, having crossed his legs, set his body straight, having mindfulness established before him [established upon his meditation subject].

Then The Buddha explains mindfulness-of-breathing (ānāpāna-sati):

He mindfully breathes in; mindfully breathes out.

1. Breathing in long, he understands: ‘I breathe in long;’ breathing out long, he understands: ‘I breathe out long.’

2. Breathing in short, he understands: ‘I breathe in short;’ breathing out short, he understands: ‘I breathe out short.’

3. ‘Experiencing the whole [breath] body, I shall breathe in’: thus he trains; ‘experiencing the whole [breath] body, I shall breathe out’: thus he trains.

4. ‘Tranquillizing the body-formation, I shall breathe in’: thus he trains; ‘tranquillizing the body-formation, I shall breathe out’: thus he trains.

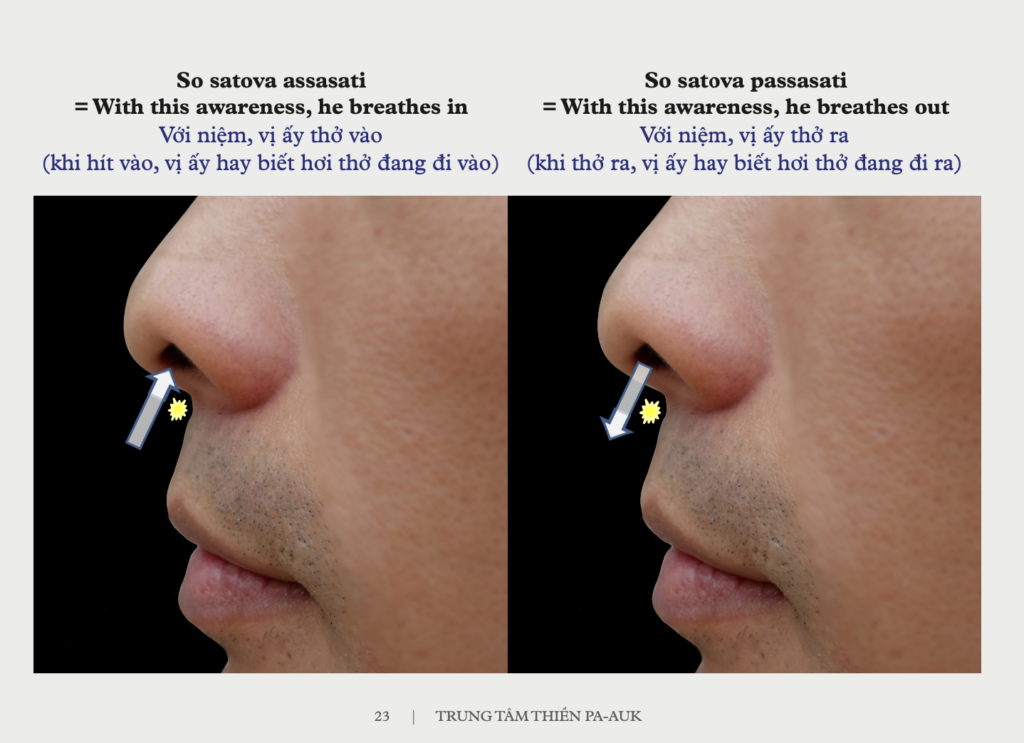

To begin meditating, sit in a comfortable position and try to be aware of the breath as it enters and leaves the body through the nostrils. You should be able to feel it either just below the nose or somewhere around the nostrils: that is called the touching-point. Do not follow the breath into the body or out of the body, because then you will not be able to perfect your concentration. Just be aware of the breath at the most obvious place it brushes against or touches, either the top of the upper lip or around the nostrils. Then you will be able to develop and perfect your concentration.

Do not pay attention to the natural characteristics (sabhāva-lakkhaṇa), general characteristics (sammañña-lakkhaṇa),[2] or colour of the nimitta (sign of concentration). The natural characteristics are the characteristics of the four elements in the breath: hardness, roughness, flowing, heat, supporting, pushing, etc. The general characteristics are the impermanent (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and non-self (anatta) characteristics of the breath. This means, do not note ‘in-out-impermanent’, or ‘in-out-suffering’, or ‘in- out-non-self’. Simply be aware of the in & out breath as a concept.

The concept of the breath is the object of ānāpāna-sati. It is this object you must concentrate on to develop concentration. As you concentrate on the concept of the breath in this way, and if you practised this meditation in a previous life, and developed some pāramī, you will easily be able to concentrate on the in & out breath.

If not, the suggests counting the breaths. You should count after the end of each breath: ‘In-out-one, in-out-two,’ etc.[3]

Count up to at least five, but to no more than ten. We suggest you count to eight, because that reminds you of the Noble Eightfold Path, which you are trying to develop. So you should count, as you like, up to any number between five and ten, and determine that during that time you will not let your mind drift, or go elsewhere, but be only calmly aware of the breath. When you count like this, you find that you are able to concentrate your mind, and make it calmly aware of only the breath.

After concentrating your mind like this for at least half an hour, you should proceed to the first and second stage of the meditation:

(1) Breathing in long, he understands: ‘I breathe in long (dīghaṁ assasāmi);’ breathing out long, he understands: ‘I breathe out long (dīghaṁ passasāmi).

(2) Breathing in short, he understands: ‘I breathe in short (rassaṁ assasāmi);’ breathing out short, he understands: ‘I breathe out short (rassaṁ passasāmi).

At this stage, you have to develop awareness of whether the in & out breaths are long or short. ‘Long’ or ‘short’ here do not refer to length in feet and inches, but length in time, the duration. You should decide for yourself what length of time you will call ‘long’, and what length of time you will call ‘short’. Be aware of the duration of each in & out breath. You will notice that the breath is sometimes long in time, and sometimes short. Just knowing this is all you have to do at this stage. Do not note, ‘In-out-long, In-out-short‘, just ‘In-out’, and be aware of whether the breaths are long or short. You should know this by being just aware of the length of time that the breath brushes against and touches the upper lip, or around the nostrils, as it enters and leaves the body. Sometimes the breath may be long throughout the sitting, and sometimes short, but do not purposely try to make it long or short.

At this stage the nimitta may appear, but if you are able to do this calmly for about one hour, and no nimitta appears, you should move on to the third stage:

(3) ‘Experiencing the whole [breath] body (sabba-kāya-paṭisaṁvedī), I shall breathe in (assasissāmi):’ thus he trains.

‘Experiencing the whole [breath] body (sabba-kāya-paṭisaṁvedī), I shall breathe out (passasissāmī):’ thus he trains.

If you are calmly aware of the breath from beginning to end for about an hour, and no nimitta appears, you should move on to the fourth stage:

(4) ‘Tranquillizing the body-formation (passambhayaṁ kāya-saṅkhāraṁ), I shall breathe in (assasissāmi):’ thus he trains.

‘Tranquillizing the body-formation , I shall breathe out (passasissāmī):’ thus he trains.

To do this, you should decide to make the breath tranquil, and go on being continuously aware of the breath from beginning to end. You should do nothing else, otherwise your concentration will break and fall away.

The gives four factors for making the breath tranquil:[4]

1. Concern (ābhoga)

2. Reaction (samannāhāra)

3. Attention (manasikāra)

4. Reviewing (paccavekkhaṇa)

And they are explained first with a simile:

Suppose a man stands still after running or after descending from a hill, or putting down a load from his head; then his in-breaths and out-breaths are gross, his nostrils become inadequate, and he keeps on breathing in and out through his mouth. But when he has rid himself of his fatigue and has bathed and drunk and put a wet cloth on his chest, and is lying in the cool shade, then his in-breaths and out-breaths eventually occur so subtly that he has to investigate whether they exist or not.

Likewise, says the Visuddhimagga, the bhikkhu’s in&out-breaths are gross to begin with, become increasingly subtle, after which he has to investigate whether they exist or not.

To further explain why the bhikkhu needs to investigate the in&out-breaths, the Visuddhimagga says:

Because previously, at the time when the yogi had not yet discerned [the in&out breath] there was no concern in him, no reaction, no attention, no reviewing, to the effect that [he knew]: ‘I am progressively tranquillizing each grosser bodily formation [the in&out breath].’ But once he has discerned [the in&out breath], there is. So his bodily formation [the in&out breath] at the time when he has discerned [it] is subtle in comparison with what it was at the time when he had not [discerned it].

1. Concern (ābhoga): you pay initial attention to the breath, you apprehend the breath, you advert the mind towards the breath, to the effect: ‘I will try to make the breath tranquil.’

2. Reaction (samannāhāra): you continue to do so, i.e. you pay sustained attention to the breath that way, do it again and again, keep the breath in the mind, to the effect: ‘I will try to make the breath tranquil.’

3. Attention (manasikāra): literally ‘deciding to make the breath tranquil’. Attention is the mental factor that makes the mind advert towards the object. Attention makes the mind conscious of the breath and know the breath.

4. Reviewing (paccavekkhaṇa):[5] you review (vīmaṁsa) the breath, make it clear to the mind, to the effect: ‘I will try to make the breath tranquil.’

So all you need to do at this stage is to decide to tranquil the breath, and to be continuously aware of it. That way, you will find the breath becomes more tranquil, and the nimitta may appear.

Just before the nimitta appears, a lot of yogis encounter difficulties. Mostly they find that the breath becomes very subtle and unclear; they may think the breath has stopped. If this happens, you should keep your awareness where you last noticed the breath, and wait for it there.

A dead person, a fetus in the womb, a drowned person, an unconscious person, a person in the fourth jhāna person in the attainment of cessation (nirodha samāpatti) [6], and a brahmā: only these seven types of person do not breathe. Reflect on the fact that you are not one of them, that you are in reality breathing, and that it is just your mindfulness which is not strong enough for you to be aware of the breath.

When it is subtle, you should not make the breath more obvious, as the effort will cause agitation, and your concentration will not develop. Just be aware of the breath as it is, and if it is not clear, simply wait for it where you last noticed it. You will find that, as you apply your mindfulness and wisdom in this way, the breath will reappear.

Notes:

[1] D.ii.9 ‘The Great Mindfulness-Foundation Sutta’ (Also M.I.i.10)

[2] NATURAL CHARACTERISTIC (sabhāva-lakkhaṇa): the characteristic peculiar to one type of ultimate reality, be it materiality or mentality: also called individual characteristic (paccatta-lakkhaṇa); general characteristic (samañña-lakkhaṇa): the three characteristics general to all formations, be they material or mental: impermanence, suffering, non-self.

[3] VsM.viii.223ff ‘Ānāpāna-sati-kathā’ (‘Mindfulness-of-Breathing Discussion’) PP.viii.90ff

[4] VsM.viii.220 ‘Ānāpāna-sati-kathā’ (‘Mindfulness-of-Breathing Discussion’) PP.viii.178

[5] Here, vimaṁsa is synonymous with paccavekkhaṇa, and is the term employed in the sub-commentary’s discussion.

[6] When consciousness, associated mental factors, and materiality produced by consciousness are suspended. For details regarding this attainment, see Q&A 5.1, p.173.

Knowing and Seeing – Pa Auk Sayadaw